post includes spoilers for Psycho (1960), Hereditary (2018) and The Witch (2015)

“We ate the birds. We ate them. We wanted their songs to flow up through our throats and burst out of our mouths, and so we ate them. We wanted their feathers to bud from our flesh. We wanted their wings, we wanted to fly as they did, soar freely among the treetops and the clouds, and so we ate them” -Margaret Atwood

Feathered creatures, swooping about unpredictably, singing bright songs, low and mournful songs, croaking raw and vicious laughter songs. Birds have held a deep fascination for many throughout history, in both their natural habits and behaviors and in the process of divining meaning, observing symbols and inspiring lore. Birds sail to the heavens, ethereal beings that dare to kiss the highest regions. Contrary to this angelic and divine representation, birds can also be predatory, vicious and dangerous. They can signify darkness and evil; scavenger birds feast upon death, circling above to herald the very expiration of their next meal.

Many different species of birds appear in literature, dating back centuries. Some notable avifauna are Poe’s titular Raven, an ominous presence above the bleak chamber door. The legend of the harpies, monstrous women with feathered bodies. Swans appear in a wealth of fairy tales, evoking grace and beauty. Charlotte Perkins Gilman’s heroine in The Yellow Wallpaper is infantalized and referred to as ‘little goose’, a silly, childish being, unworthy of consideration. The witch Baba Yaga lives in a wicked home upon chicken legs.

In her inimitable text, The Monstrous Feminine (Routledge, 1993), Barbara Creed discusses the connection between birds and the archetype of the castrating mother. In Alfred Hitchcock’s Psycho (1960) Mother Bates is cast as a birdlike figure, insofar as she is literally stuffed and sewn, like Norman’s taxidermied birds. Creed writes, “The birds in his parlour are birds of prey; they hover menacingly overhead as if about to pounce on their victims. Norman has frozen them in time at the very moment when they are poised, motionless, just prior to the kill. This form of passivity is not associated with lack of will as one might expect, but with the opposite, with the power and aggressivity of a killer ready to strike. “

Horror fans are keenly aware of Hitchcock’s other classic film, The Birds (1963), which cast the skies in a cloud of menace, agitating ornithophobia worldwide. Of this film, Creed writes, “the birds may also be understood as fetish-objects, not of the castrated/phallic, but of the castrating mother.” Many films have chosen birds as devious villains or mindless pecking swarms of violence. But what of the less pervasive bird imagery that pervades the genre even still? This post will explore some of the bird symbology that appears within horror, and in particular, how it connects to women.

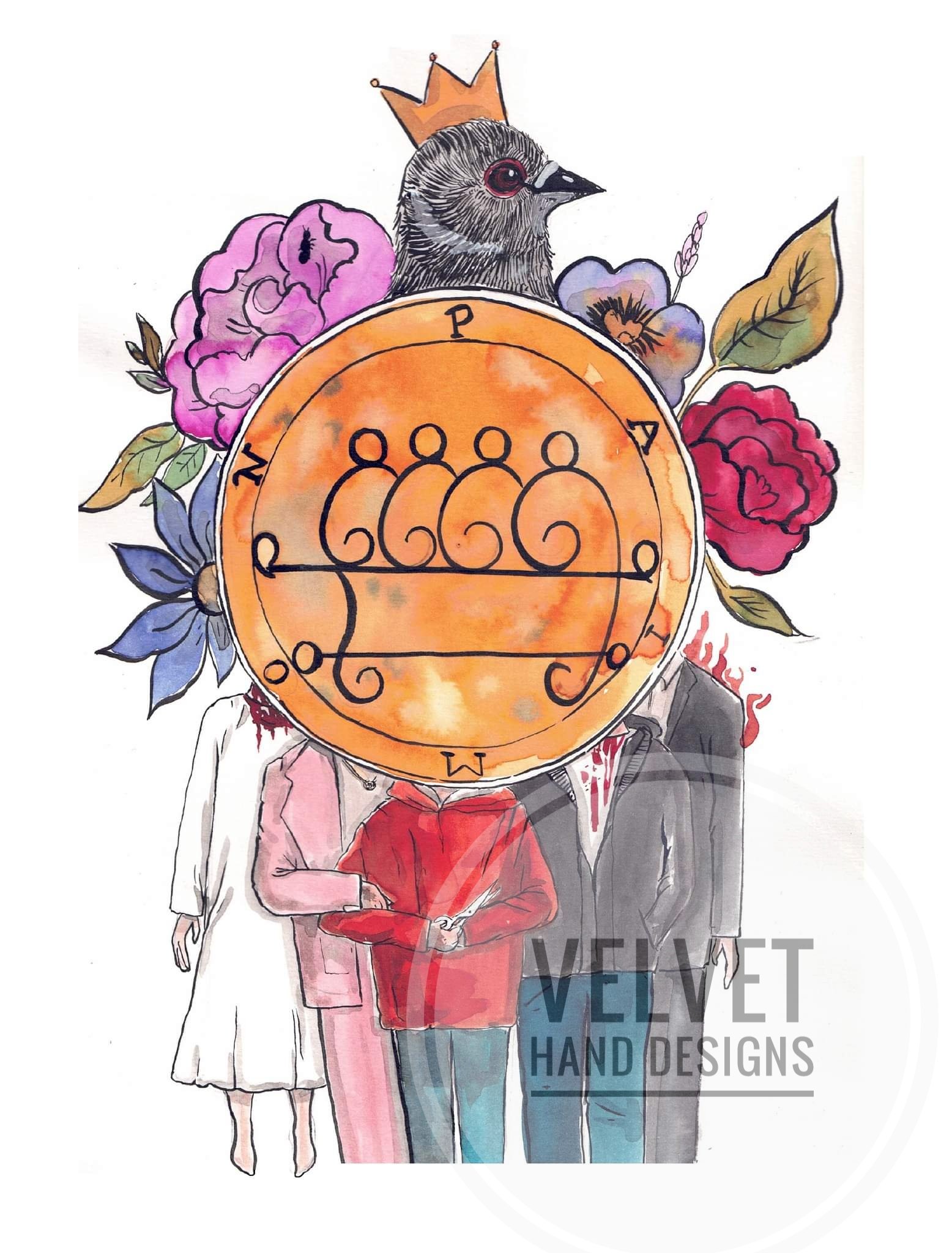

Let’s talk about bird imagery in Ari Aster’s 2018 Hereditary. The film centers around a family in the wake of a maternal grandmother’s death, as they are plagued not only by grief, but by the looming presence of a nefarious pagan cult. Adolescent daughter, Charlie (Milly Shapiro) is an outcast, an odd duck , if you will (groan.) In the film, we see her in class with her peers as a pigeon strikes the window with force. The students are surprised and exclaim. Charlie doesn’t react. We next watch her decapitate the bird with a pair of scissors; her face stoic and without emotion. She later creates a sort of doll-totem out of the bird’s head, a macabre companion or idol. This avian decapitation can be seen to foreshadow Charlie’s own impending decapitation, as well as that of her mother and grandmother. In the dichotomy of the cult, the male child is the prized child, a suitable host for the demon Paimon. Thus, the female family members, while a necessary factor, are ultimately dispensable. Likewise, pigeons themselves, while common and widely known , are often seen as unclean, diseased, synonymous with refuse. The pigeon represents an unpleasant thing, one which we may have to coexist with but prefer to distance from.

Pigeons are also known for their homing and navigational abilities. This behavior is mirrored in the scene in which a decapitated Annie (Toni Collette) literally flies towards the nest/roost/perch of the family’s tree house. Her mother’s form also manages to navigate it’s way ‘back home’ from the cemetery, homing in on the nexus of the cult.

Charlie herself participates in a tick-like gesture of emitting a clicking sound from her mouth. Her pops and clicks are used to great eerie effect throughout the film, triggering an unsettling feeling. At one point, we hear her trademark click after her death, implying that her being is somehow passively watching the family. Common Ravens are known to make clicking or knocking calls, which may be used to assist in location. Charlie, perhaps, calls the cult members to towards the crumbling family with her unearthly clicks.

The next horror bird imagery I’ll explore is within Robert Egger’s 2015 film The Witch. Much has been analyzed and written about this horror drama. The film tells the mournful tale of an ultra orthodox Puritan family besieged by the threat of witchcraft. Near the film’s opening, lead character Thomasin (Anya Taylor-Joy) cares for the family’s infant child as her parents work the field. Under her watch, the child somehow vanishes, triggering a series of events that lead to the family’s suspicions that Thomasin is a witch.

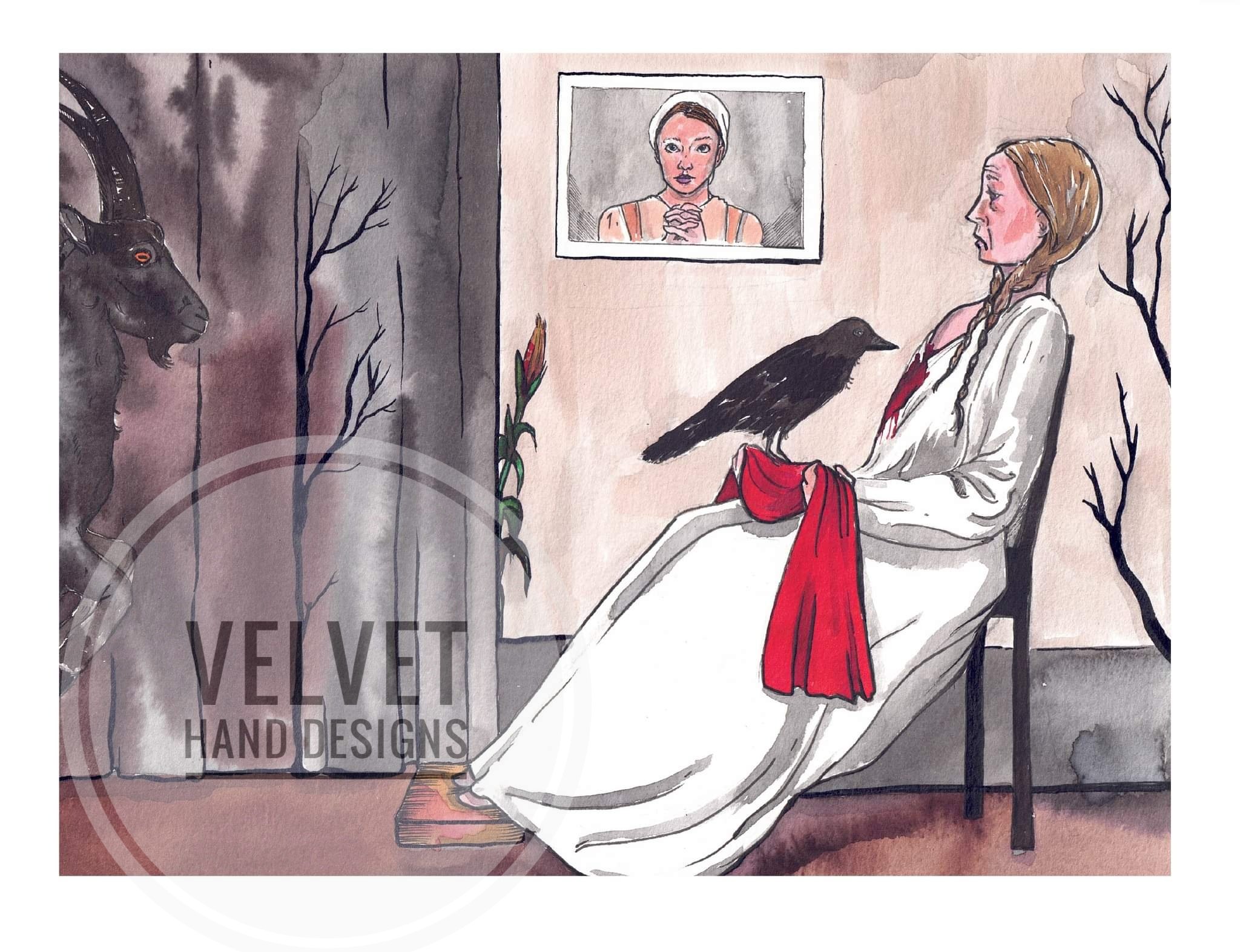

The family’s matriarch, Katherine (Kate Dickie) is understandably devastated after the loss of her child. We witness her rage, her fear and her sorrow. Katherine experiences a dream/hallucination in which her infant is returned to her. She nurses the precious baby at her breast, when suddenly it is revealed that Katherine is, in effect, nursing a crow or raven. The bird pecks and tears viscerally at her chest as she laughs, unhinged and broken.

Ravens and crows, while different species, both fall in the corvidae family. They share similar lore, much of it tied to death. German mythology indicates that ravens are damned souls, while Swedish legend suggests them to be spirits of the dead (The Hidden Meaning of Birds, Arin Murphy-Hiscock, Simon & Schuster, 2019). They’ve been associated with mimicry, trickery and an uncanny intelligence. It is said that the crow is tied to the underworld, a harbinger of death, possibly due to it’s habit of surviving on carrion, and it’s place in the natural cycle of decomposition.

Perhaps, the presence of the child-crow in The Witch indicates that Katherine is no longer any more than carrion. She is the living dead, emotionally broken and beyond rescue. The bird feasts upon her, like the carcass of an animal, even as she laughs and breathes, because she is fully fractured.

Crows and ravens are also tied to the occult and witchcraft, often portrayed as a witch’s familiar. As creatures with high intelligence, the birds would serve as useful partners for witches. In her work The Witch in History: Early, Modern and Twentieth-Century Representations (Routledge, 1996) Diane Purkiss writes of the witch as ” a perverse kind of mother”, describing the figure as possessing a witch’s teat or witchmark from which a familiar may nurse. She notes “Early modern medical writers believed that breastmilk was the blood which has been nourishing the foetus in the womb, drawn up to the breasts via a large vein and purified into milk. ”

The fear of the female body is pervasive throughout history, and we see it recognized in The Witch in the context of Thomasin’s body. As a maturing teenage female, her form becomes taboo. When we look at Katherine, we can also see the abject female form. Purkiss writes, ” The breast was a redeemed part of the open, dirty body of the childbearing woman, a part where her polluted blood was purified by maternal love,”.

There exists a fear and disgust associated with the female body and the womb. Katherine and the crow call to mind the prevalence of such fears in Puritan times that a witch may have a companion, or familiar, that she nurses. The witch, being impure, does not give milk (or milk-blood) but produces only unclean, evil blood. Purkiss states, “Her body is all poison. Her refusal or inability to purify blood into milk is also connected with her lack of milk.” She goes on to explain that the witch has commonly been deemed guilty of drying up cow’s or goat’s milk, even turning it to blood. This is acknowledged in The Witch when we see the goat produce blood in place of milk.

Does Katharine’s crow tell us that the family matriarch who holds such hatred and contempt and possesses an abject body is, herself, a witch or witch-like? Perhaps the symbol of the bird is that all women are witches, and if not, they are deeply at risk of irreversible corruption, or that woman is dangerous, capable of tearing away at a solid foundation with a series of violent pecks.

The woman-bird connection exists in a wealth of horror media (Freaks (1932), Black Swan (2010), Bird Box (2018) ….possible future explorations!) . Like the bird, woman has value in her beauty, in her aesthetic, she is a prize to be displayed. If her song can be harnessed her worth can be protected, perhaps her form will be uncorrupted. She will be placed delicately within a cage where she becomes a décor piece, a gentle song her only offering.

Conversely, perhaps woman is a calculating predator. She is unpredictable and looming, perched upon high like Poe’s raven, reminding us that we are all only soon-to-be-carrion. Her proverbial talons are fast and fierce, and as quick as she mocks and clicks, she may call the witch to the kill. The bird-woman is free to gleefully feast upon the remains.